By: Habiba C. Mohamed, country director for Kenya

Earlier this spring, I had the privilege of taking part in the launch of free fistula repair surgeries at Kapenguria County Referral Hospital in West Pokot County, Kenya. This facility was a brand-new addition to the Fistula Foundation Treatment Network (FFTN) in Kenya. The festivities that day were personally inspiring because—a little more than 40 years earlier—I was born in that very hospital.

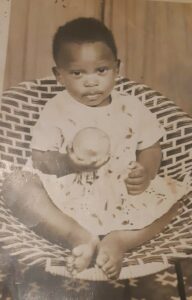

Habiba at age one (left), and more than 40 years later (right) as she returned to her birthplace—Kapenguria County Referral Hospital—this spring to celebrate the facility that is now providing free fistula care to women in West Pokot County.

As I stood on the hospital grounds, I found myself taking a trip down memory lane. Throughout the celebration, I couldn’t help but reflect on the long and winding journey that had led me back to Kapenguria.

The Path to Belonging

I circled the deserted village, looking for a family with a bull that I was supposed to check up on. It was decades ago, and I was working as a veterinarian in a private practice in Mumias, in Western Kenya. While visiting my childhood home in West Pokot, I decided to make a few housecalls. But I was late, and the household with the bull was nowhere to be found. They must have given up on me coming today, I thought.

It was often difficult for visitors like me to get approval to work in villages like this one, so I didn’t give up on finding members of that family. As I walked around a smattering of houses, a tiny face kept popping into my peripheral vision. The face would disappear as quickly as it appeared, just beyond where my eyes could see. I was making no progress in finding the family, but this face followed me wherever I turned. Finally, curiosity got the best of me.

I snuck around a house to see if I could find that little face. What I saw when I rounded the corner marked a turning point in my life.

The Moment My Life Changed

A toddler, not more than four years old, was tied to a rope that was wrapped around a house. The little boy was disabled, and had defecated on himself. Tears swelled in my eyes like a flash flood; the sight of that boy swept away everything I thought I knew about the world. As a girl, I had been protected from the harsh realities of poverty and neglect. How could someone do this to a child? I thought. All I could do at that moment was retrieve a bowl of porridge that had been placed out of the boy’s reach, and set it down at his level. He was dirty, ravenously hungry, and alone.

I left the village, but the image of that boy wouldn’t leave my mind. I had to know why. I had to learn what could have led his family to commit this injustice.

What I learned disturbed me further. The supposed offense committed by this child was to be born disabled, out of wedlock. The mother, who had brought shame to her family, was shipped away to live as a sex worker. Drawn in by the unfolding details of this horrific chain of events, I kept digging for more information.

I reached out to the mother of the boy, hoping to learn her story. Building trust was difficult, but I had made up my mind. There was a whole world that I had been protected from knowing about. Women in desperate need of help were living in my community. I couldn’t look away, and I couldn’t judge them for what they had been through. I started meeting with this mother, and with other sex workers, in order to learn what had led them to this life. Over time my meetings with these women evolved into a formal support group for women in need.

Finding My Life’s Work

This is when I first heard about fistula. The mother of the boy in the village had developed this devastating condition after enduring a prolonged, obstructed labor. The injury left her leaking, and humiliated. Such is the case for many women who give birth in rural Kenya, without help from a trained birth attendant.

What began as a deep curiosity about the lives of those less fortunate than myself eventually led to my life’s work. In 2006, I started an organization called Women and Development Against Distress in Africa (WADADIA) to advance the psychological and reproductive health of women in my community, and to empower vulnerable women through socio-economic support. WADADIA later partnered with Fistula Foundation to provide outreach and rehabilitation services to fistula patients, and I joined Fistula Foundation to manage fistula programming in Kenya.

That was eight years ago. The progress we’ve made in less than a decade—FFTN in Kenya has provided about 9,000 free surgeries to suffering women since 2014—makes my heart swell with pride. But until there are no fistula patients in my country, our work continues.

African Houses Are Never Filled

There’s a saying in my culture: “African houses are never filled.” In other words, anyone who needs a place of refuge is welcome to stay, eat, and find support in our home. My father lived by this principle. Our house was always bustling with cousins, neighbors, and others who needed a shoulder to lean on or a nonjudgmental ear to listen. My father never looked down on anybody. It didn’t matter who you were: You were always welcome in my family’s home. This ideal came from a belief that God is working through us. In taking care of others, we are being taken care of, too.

Left: Habiba (back row, in a polka-dotted dress) poses with her stepmother (middle row, in an orange head scarf), aunt (middle row, in a black head scarf), and siblings. Right: Habiba (third from left) sits in between her father and stepmother, among family members.

How I was raised, and the principles and values instilled in me by my father, no doubt led me to work in fistula programming. When FFTN in Kenya began as a pilot project in 2014, I never imagined that free fistula treatment would come to my birthplace, Kapenguria County Referral Hospital. And yet, four decades after I first escaped my mother’s womb and opened my eyes to the world in that very facility, I came back to Kapenguria to tell my community: Your daughter is home. She was listening to everything you taught her, and she is happy to contribute something to her beloved community—another link in a countrywide network of care that will help restore women’s lives.

This work is personal for me. These women are members of my community. I understand the cultural values they hold and the patriarchal society in which they live. I can empathize with them, because I was raised in the same environment. We can work together to make decisions that help them heal mentally and physically. We can help them overcome the obstacles they face, despite the horrors they have seen.

This work is my life. “Excited” would be an understatement to describe how I feel about adding Kapenguria to the network we are building. The prevalence of fistula in Kenya can’t be overstated. Far too many factors contribute to the spread of this devastating condition: From the country’s difficult terrain to failed health services, from the persistence of a patriarchal culture to the practice of female genital mutilation—it’s a really big issue. But I’ll keep rounding the corner to face the realities that lurk in the shadows. I’ll keep asking women to tell their stories and encourage them to seek help for their physical and mental wounds. I’ll keep finding women who have been cast out, offering them a warm hug and saying, “Help is here.”

I am so humbled and happy to contribute to the goal of achieving a fistula-free Kenya. For my people: My house and my heart are always open.

Published on June 14, 2022